Most migration programs fail in a familiar way: the warehouse objects move, the dashboards load, and everyone assumes the hard part is over—until the application layer starts throwing “unknown column,” “function not found,” or worse: quietly wrong results.

In many programs, the root cause isn’t the database schema or the ETL toolchain. It’s embedded SQL—the production logic living outside the database, hidden inside application code, scripts, notebooks, and orchestration glue. It’s also the easiest scope item to miss, which is why it becomes the silent killer.

What “embedded SQL” actually is (and why it’s so dangerous)

Embedded SQL is any SQL that is not managed as a first-class database object (stored procedure, view, etc.) and instead appears as:

- SQL strings in Java/.NET services (JDBC/ODBC calls)

- Query fragments assembled dynamically (

"WHERE " + filterClause) - SQL inside Python notebooks, Airflow DAGs, dbt macros, shell scripts

- SQL embedded in BI tooling exports and “temporary” utilities

- Framework “escape hatches” (ORM raw queries)

The danger is simple: this code doesn’t show up in your database inventory, and therefore doesn’t get migrated with the same discipline. Many teams treat migrations as fragmented workstreams (OLTP, OLAP, ETL, app logic) and miss the app-embedded surface area until late test cycles.

The four failure modes that make embedded SQL a “silent killer”

1) It breaks late—after you think you’re done

DDL and stored procedures often have conversion plans. Embedded SQL shows up during integration testing, UAT, or cutover rehearsal—when changes are most expensive.

2) It breaks selectively

Only certain endpoints or workflows trigger certain query paths. The result is false confidence (“most things work”) until a business-critical flow fails under real usage.

3) It creates semantic drift (the most expensive bug)

Even when queries run, semantics can change:

- join behavior changes because of null-handling differences

- date/time logic shifts subtly

- implicit casts become explicit and change results

These don’t always throw errors. They just produce different numbers.

4) It hides dependency chains you didn’t plan for

Embedded SQL often reaches across domains (“just fetch customer tier”), pulling tables you didn’t migrate yet—or calling objects that were renamed or re-modeled. Proper dependency mapping is the antidote, but you only get that if you discover embedded SQL as part of the inventory.

Where embedded SQL hides (a quick mental model)

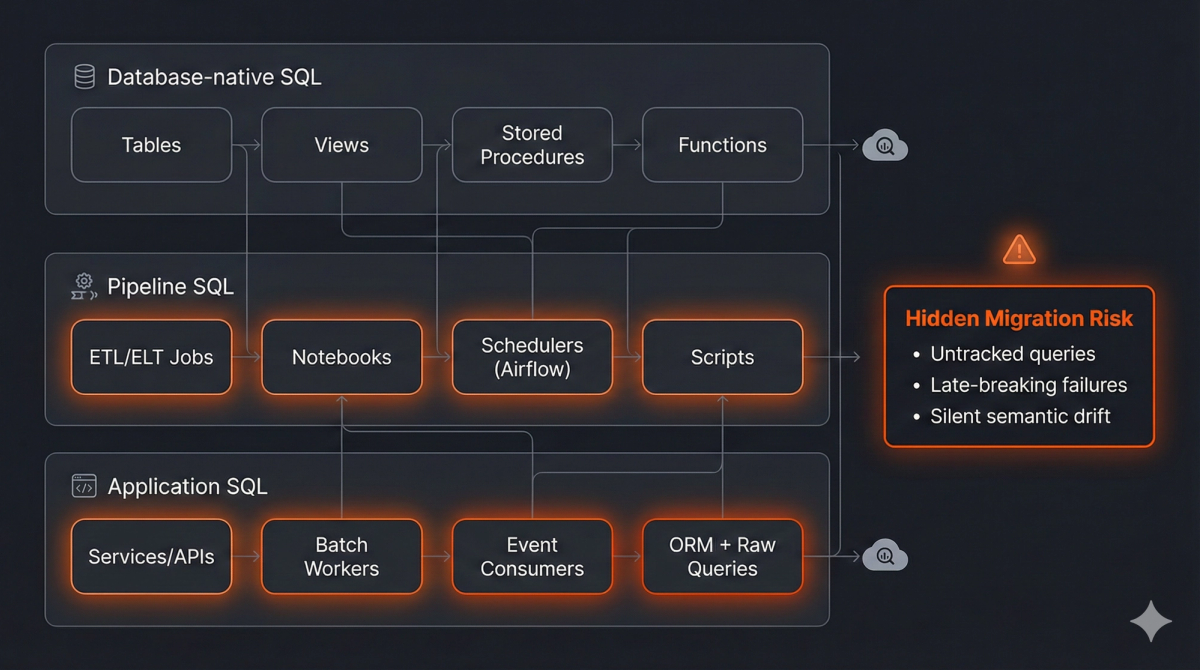

If you want a practical way to think about this, map SQL to three “homes”:

- Database-native SQL: views, SPs, functions (you can inventory these easily)

- Pipeline SQL: ETL/ELT tooling, notebooks, orchestration

- Application SQL: services, APIs, batch jobs, event consumers

Most teams do (1) well, do (2) inconsistently, and discover (3) late. A migration plan that doesn’t treat all three as first-class migration units is essentially betting the cutover on luck.

The fix: make embedded SQL “discoverable” before you migrate

The most reliable programs do two things early:

A) Extract a code-and-metadata bundle, not just schema

You need standardized exports and manifests so you can prove what you captured—and what you didn’t. This is why we bias toward export bundles with source-of-truth manifests (checksums + lineage) rather than ad-hoc zips from five teams.

B) Score and map dependencies across objects (including embedded SQL)

Once you ingest the inventory, you can score complexity and build a dependency graph that informs waves, gating, and acceptance criteria.

This “discover first” posture is also why we position migrations as a program with assessment → blueprint → conversion → validation, rather than a one-off translation sprint.

Converting embedded SQL at scale: treat it as a conversion path, not an exception

Embedded SQL is rarely “just SQL.” It’s SQL plus host-language constructs: string assembly, conditional branches, loop-driven pagination, and runtime parameterization.

That’s why a serious factory needs explicit support for dynamic/hosted SQL rewrite, where the system rewrites host constructs and converts the embedded SQL in the same pass.

In our conversion system, this sits alongside the standard conversion types (DDL→DDL, SP→SP, Query→Query), and is orchestrated with multi-file execution, review markers, and validation gates.

Validation: the only way to catch “silent” breakage

If embedded SQL is the silent killer, validation is the smoke detector.

At minimum, you want:

- dialect-aware syntax validation

- catalog cross-checks (tables/columns exist, names resolved)

- selective non-prod execution for smoke tests

- review markers to focus human attention where automation is least reliable

The key is not “test everything manually.” The key is to use automation to narrow the review surface area so humans spend time on the hardest 10–20% rather than re-reading the easy 80%.

A pragmatic checklist for your next migration sprint

Use this as a quick readiness gate before you declare scope “under control”:

- Do you have a repository-level inventory of SQL-bearing files?

(apps, jobs, notebooks, scripts—not just database objects) - Can you quantify embedded SQL volume by domain/service?

(count, complexity score, change frequency) - Do you have cross-layer dependency mapping?

(embedded SQL → tables/views → downstream reports/jobs) - Is dynamic SQL treated as a first-class conversion path?

(not “we’ll fix that manually later”) - Do you have validation gates that catch semantic drift risks?

(catalog checks + targeted execution + review markers)

If you can’t answer “yes” to most of these, embedded SQL is very likely sitting in your critical path—whether you’ve planned for it or not.

Closing: make embedded SQL visible, or it will make your risk visible

Cloud migrations are rarely blocked by “hard SQL.” They’re blocked by untracked logic—the SQL you didn’t know you owned.

Treat embedded SQL as a first-class scope item from day one, and your migration becomes a managed program with waves, gates, and predictable cutover. Ignore it, and you’ll still migrate—just with a lot more late nights and a lot less certainty.